Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common malignant tumour affecting the urinary system. In 2020, it ranked fourth in incidence among all cancers, comprising 7.3% of all new cancer cases. Notably, PCa was the second most frequently diagnosed cancer in men globally, accounting for 14.1% of new cancer cases in males1.

Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer (CRPC) is characterised by disease progression despite androgen deprivation therapy, with serum testosterone maintained at castration levels. Disease progression can be monitored through prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing or imaging evidence2.

Metastasis occurs when cancer spreads from its original site to distant parts of the body. Metastatic PCa includes metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer (mHSPC) and metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). These subtypes of metastatic PCa exhibit the characteristics of hormone sensitivity2.

Generally, CRPC is relatively late-stage of the disease.

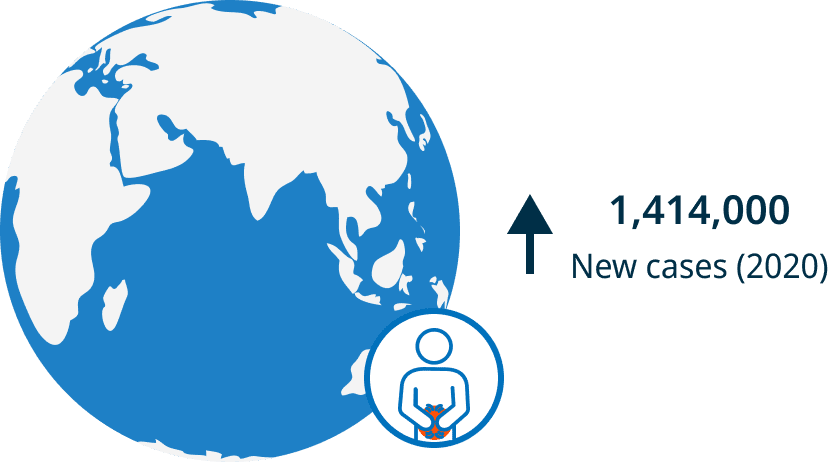

In 2020, there were over 1,414,259 estimated new cases of PCa worldwide, with an age-standardised incidence of 37.5 per 100,000 males in higher human development index countries1.

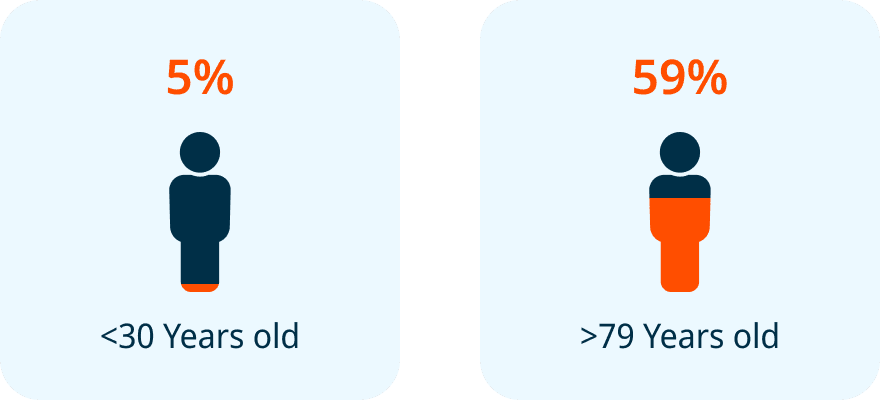

5% (3-8%) prevalence at age <30 years to a prevalence of 59% (48-71%) by age >79 years3.

PCa also significantly contributes to cancer-related deaths, with 375,304 deaths in 2020 worldwide, positioning as the fifth most common cause of cancer-related mortality in men1.

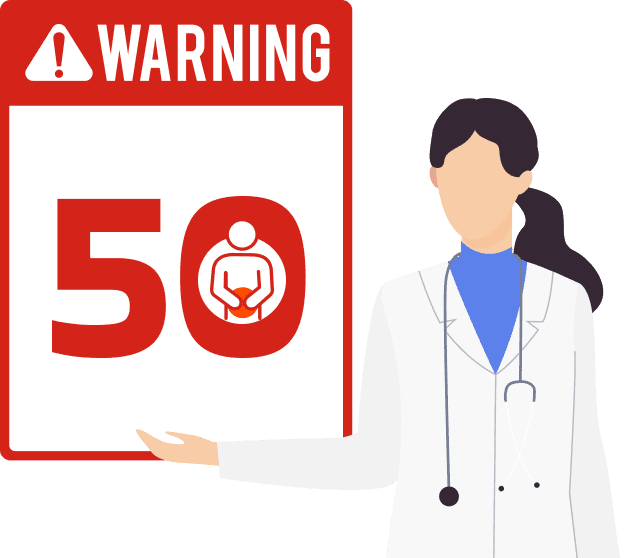

Subclinical prostate cancer, the presence of prostate cancer with no noticeable symptoms, is common in men >50 years2.

1Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-49.

2Horwich A, Parker C, Bangma C, Kataja V. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2010;21 Suppl 5:v129-33.

3Bell KJ, Del Mar C, Wright G, Dickinson J, Glasziou P. Prevalence of incidental prostate cancer: A systematic review of autopsy studies. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1749-57.

4Gandaglia G, Leni R, Bray F, Fleshner N, Freedland SJ, Kibel A, et al. Epidemiology and Prevention of Prostate Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2021;4(6):877-92.

5Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C. Fried food and prostate cancer risk: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2015;66(5):587-9.

6Liss MA, Al-Bayati O, Gelfond J, Goros M, Ullevig S, DiGiovanni J, et al. Higher baseline dietary fat and fatty acid intake is associated with increased risk of incident prostate cancer in the SABOR study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2019;22(2):244-51.

7Gacci M, Russo GI, De Nunzio C, Sebastianelli A, Salvi M, Vignozzi L, et al. Meta-analysis of metabolic syndrome and prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2017;20(2):146-55.

8Lian WQ, Luo F, Song XL, Lu YJ, Zhao SC. Gonorrhea and Prostate Cancer Incidence: An Updated Meta-Analysis of 21 Epidemiologic Studies. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:1902-10.

9Russo GI, Calogero AE, Condorelli RA, Scalia G, Morgia G, La Vignera S. Human papillomavirus and risk of prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Male. 2020;23(2):132-8.

10Rebbeck TR, Devesa SS, Chang BL, Bunker CH, Cheng I, Cooney K, et al. Global patterns of prostate cancer incidence, aggressiveness, and mortality in men of african descent. Prostate Cancer. 2013;2013:560857.

11Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N, An Y, Barocas D, Bitting R, et al. Prostate Cancer, Version 4.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(10):1067-96.

12Horwich A, Parker C, de Reijke T, Kataja V. Prostate cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 6:vi106-14.

13Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Brunckhorst O, Darraugh J, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer-2024 Update. Part I: Screening, Diagnosis, and Local Treatment with Curative Intent. Eur Urol. 2024.